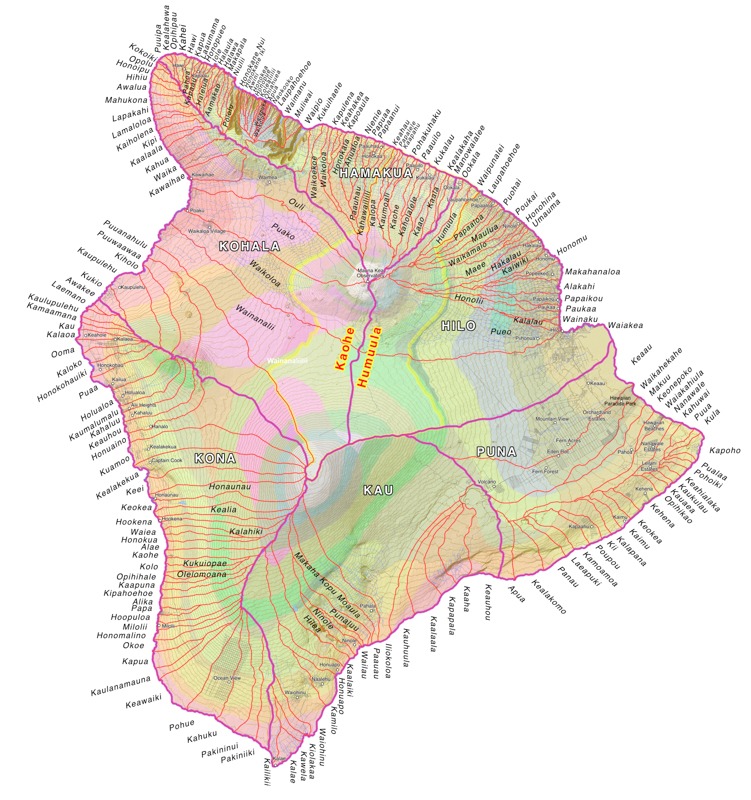

Before European settlers, led by Captain Cook, arrived to the Islands of Hawaii in 1778, the land was divided following a complex system, governed by the highest chief or king. An island (mokupuni, in hawaiian) was divided into several smaller parts (moku), and each moku was divided into narrower sections of land that ran from the mountains to the sea (ahupua`a). The size of the ahupua`a depended on the resources of the area. Poorer agricultural regions were divided into larger ahupua`a to compensate for the relative lack of natural abundance. Each ahupua`a was ruled by a local chief (ali`i). The corners of these sections of land were marked by altar rocks (ahu). The mountain tops were considered sacred ground, and was not included in any ahupua’a. The system was based on fair share, to ensure that everyone got a piece of everything, since different types of resources were found throughout the varying landscape. After the arrival of the Europeans many of the large ahupua’a have been divided and made into private property, a concept that previously did not exist in Hawaii.

Predating the early Polynesians, as legend has it, the Menehune inhabited these islands. Supposedly, they were a dwarf-like folk, superb craftspeople and very skilled at building with rock. The creation of the Alekoko fishpond is credited to the Menehune and according to legend happened overnight. Supposedly, a Menehune would not build something unless it lasted for a very long time, and always in a single nights time. No physical evidence has been found of their existence, and the term may actually have come with Tahitian settlers, who used the word manahune in a derogatory manner towards people of lower social status. Hence the term may have been adapted to earlier Hawaiian settlers, and reinforced with the arrival of Europeans, as they could have picked up the term from earlier contact with Tahiti. In both cases the oppressed had often fled into hiding in the mountains. One thing is for certain: there are a lot of loose rocks on these volcanic islands and for any construction to last long here it would have to be masterfully built, as the forces of nature are very strong.

People refer to the place currently owned by Kathleen Harrison and Botanical Dimensions, as ‘the Hill’. It is located uphill (mauka) along a patchy driveway, and is situated at the very top of the section of land according to the ahupua’a system. Being at an elevation of 670 meters above sea level means that the local climate can differ greatly from the coast. Often it is sunny during the morning, cloudy around midday, with intermittent rain during the afternoon, clearing up once more in the evening. We noted that despite the weather being sunny and clear in Kailua-Kona, the Hill tends to be hidden inside a cloud.

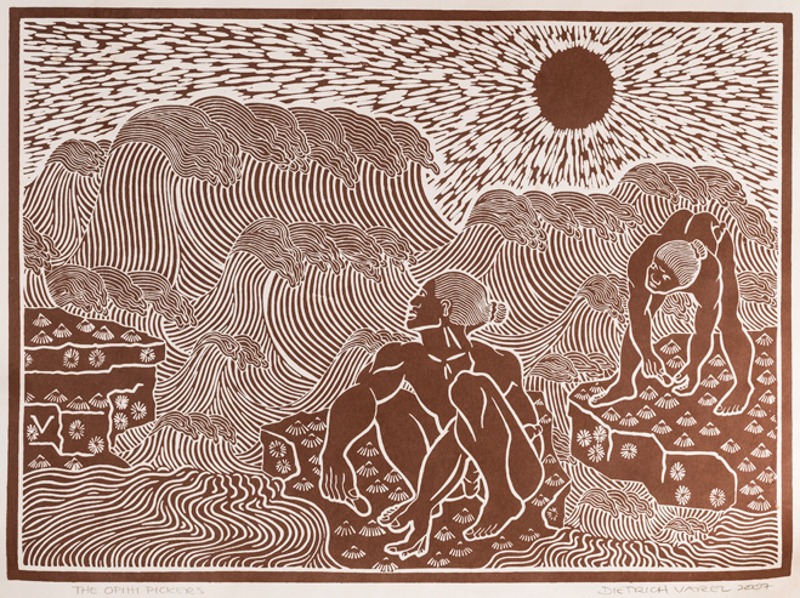

In consideration of the ahupua’a, the Hill is closest to the sacred mountain out of all the properties along the driveway, and a curious phenomenon takes place here. Interestingly another meaning of the word Opihi (see image above) is to hear, and seemingly as air flows uphill past the Hill it carries sound with it. When conditions are right we could hear drums and people speaking, as if they were in the garden, yet nowhere to be seen. Another noteworthy phenomena is the view from the Hill, which changes from being only tens of meters (on a cloudy day), to seeing Kailua-Kona (the nearest city about 60 km away), and even Maui which is around 170 km away (on a clear day). When conditions were great we could make out the silhouette of the island Moloka’i, over 200 km away, from the balcony.

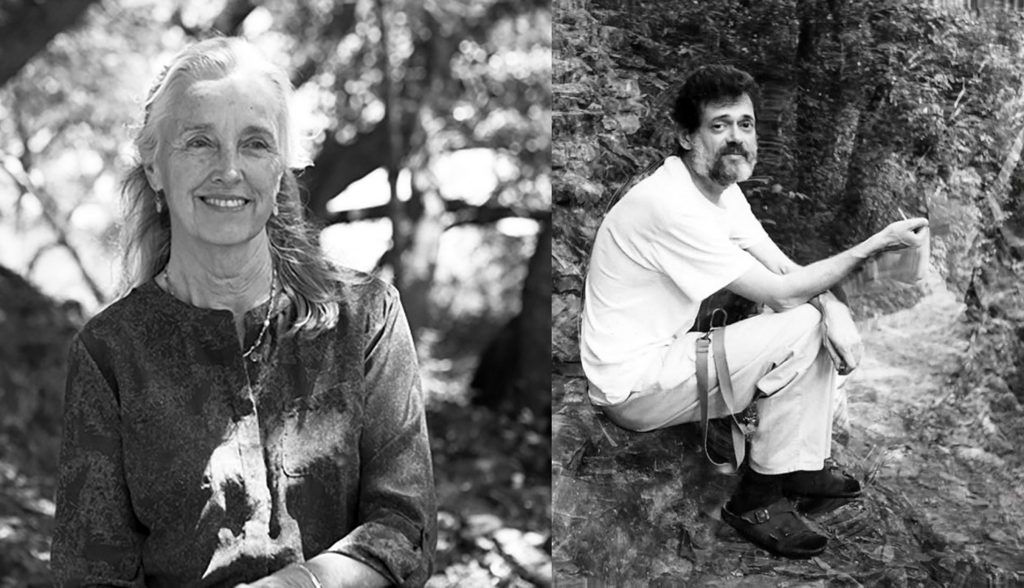

The Harrison-McKenna family have been highly prominent figures within the realms of ethnobotany, mysticism and the psychedelic movement since the 1960’s, having published multiple books, given talks, and orchestrated educational programmes. Together they founded Botanical Dimensions in 1985, which also has branches in California and Peru. Unfortunately, the current state of this promising venture (as far as the Hill in Hawaii is concerned) is rather dilapidated. The duo divorced in 1992, resulting in Terence establishing a home for himself below the trail of Botanical Dimensions, while Kathleen remained in the residence above it. Kathleen has since been the president and managing director of Botanical Dimensions. Between 1990 and 1996, Botanical Dimensions published the newsletter Plant Wise on the topic of ethnobotany. This newsletter was sold by subscription to supporters of Botanical Dimensions, and was widely appreciated, reaching as far as the New York Times. Sadly, Plant Wise was discontinued due to financial restraints.

Terence was diagnosed with cancer in 1999 and passed away in April 2000, at age 53, leaving his brother Dennis, ex-wife Kathleen, and two children Finn and Klea, to continue the legacy he left behind. His death was highly untimely and even though his insightful words can still be heard in recorded talks on youtube, and echoing in modern songs to the amusement and education of younger generations, the physical work that a place like Botanical Dimensions requires has not been picked up to a satisfactory extent.

The need for assistans is greater than ever before – if the call for aid goes unheard for much longer, the house on the Hill will have come crashing down, the trail returned to the wild jungle, and any sign of human development here retired to the annals of history. We can only hope that the sites in California and Peru are doing better than the Hill in Hawaii. It would be such a shame to witness many of the accomplishments by the Harrison-McKenna family rot away like mushrooms unpicked and left to decay. The secrets of the world they carried once more lost and forgotten.

With our project, Stomata 2020, we sincerely wish to contribute to the visions of Botanical Dimensions and its creators. During the time spent on site, we have done some basic management of the trail and garden, but considering the great need, our efforts are barely worth mentioning. We hope that our project will join the ranks of many small nudges, which may return Botanical Dimensions to its former days of glory. Therefore we plead and pray that more friends and allies find ways to contribute to the great work of the pioneers that have brought us the secrets of worldsviews lost and civilizations forgotten.

To donate simply follow this: http://botanicaldimensions.org/donate-to-BD/

References: