In this chapter we explore the different designs of the Hill and Botanical Dimensions. We will take a look at the off-the-grid house and its systems, the trail, the shelter, and a landscape architectural design, proposed by Elizabeth Hutchinson in 1985.

An off-the-grid house is – as the name entails – not connected to the infrastructural grid of public utilities, such as: electricity; water; waste; heating; communication; and so on. Hence, all of these things need to be organised using alternative methods and designs. Of course all of our ancestors have lived off-the-grid for countless generations and many people still do today, as the “grid” is a type of infrastructure emanating from urban development during the last few centuries. It is a combination of architecture and engineering, which has made it possible to create the urban and suburban environments of today. Modernist architecture has utilised recent technological advancements to create structures for human co habitation on a larger scale – cities – which were unthinkable in earlier civilisations. In many ways cities are a great solution for human habitat development, yet in many others not. The development of the infrastructural grid requires a lot of resources, and often leads to the devastation and fragmentation of the wild landscape. We are becoming increasingly aware of how big an impact our environment has on our lives. The impact can be astonishingly positive when we find ourselves in the natural wilderness, as opposed to the stressful concrete jungles of cities. Off-the-grid dwellings have a radically smaller impact on the existing environment and its ecosystems. In terms of architectural style, the dwellings are more of a Vernacular style, where constructions and designs are created simply to provide human beings with their basic necessities and appropriate form of shelter considering the context, as well as made from locally sourced materials[2].

The residence on the Hill is heated by a cast iron fireplace and electricity is provided by solar panels. It has a rain water catchment with two tanks. The first one is collecting the rainwater from the house and carport roofs, from here the water is pumped uphill to the second tank which is feeding water, by gravity, to the kitchen and shower (see map of trail further down). Water is heated by the solar panels and a gas burner when needed. The kitchen stove uses gas, the toilet is an outhouse placed above a large lava tunnel, house hold waste is taken to a local sorting station, and organic waste is composted on-site. This setup certainly does come with limitations. Many evenings we have run out of electricity and been forced to stop working at dusk. The water is undrinkable, to say the least, as there are no filters and there are a range of diseases and horrific parasites to watch out for here in the tropics. Most notable is perhaps the Angiostrongyliasis (or rat lungworm disease), which is spread by slugs that have made their way into water tanks as well as onto fruits, vegetables and leafy greens [3].

Considering the vision of Botanical Dimensions, the location was key to the feasibility in creating this repository of plants species adapted to similar climates and conditions around the world. Thanks to off-the-grid technologies and designs this dream has become reality. The quality of this system can absolutely be improved upon, as there are many off-the-grid dwellings that do not run out of power or experience other discrepancies to the comfort of its residents. But considering that this place is perched on the slopes of the most massive mountain in the world, that is an active volcano surrounded by tropical jungle, the level of comfort is quite reasonable. Comparing with the jungle journeys undertaken by many ethnobotanists and other pioneering scientists, our mission to explore the hidden layers of nature here is comparatively luxurious. Hence it is with gratitude, despite the challenges, that we are dedicated to this project and with high hopes that our work will support Botanical Dimensions in many ways. For the value of what Kathleen and Terence, together with friends and family members, have created is growing all the more invaluable as we watch the forests being clear-cut and burned at a higher rate than ever.

“We created a wide, winding trail from our clearing down the mountain, through the forest land of BD, for the purpose of planting maturing specimens of rare medicinal plants alongside it, just as they often grow trailside in their native habitat. Until the mid 1990s, authorised plant collectors sent or carried living plant specimens to this land, from Peru, Ecuador, Mexico, Costa Rica, Belize, Kenya and Thailand. When possible, traditional lore and folk names were collected along with the plants.”[4]

Kathleen Harrison

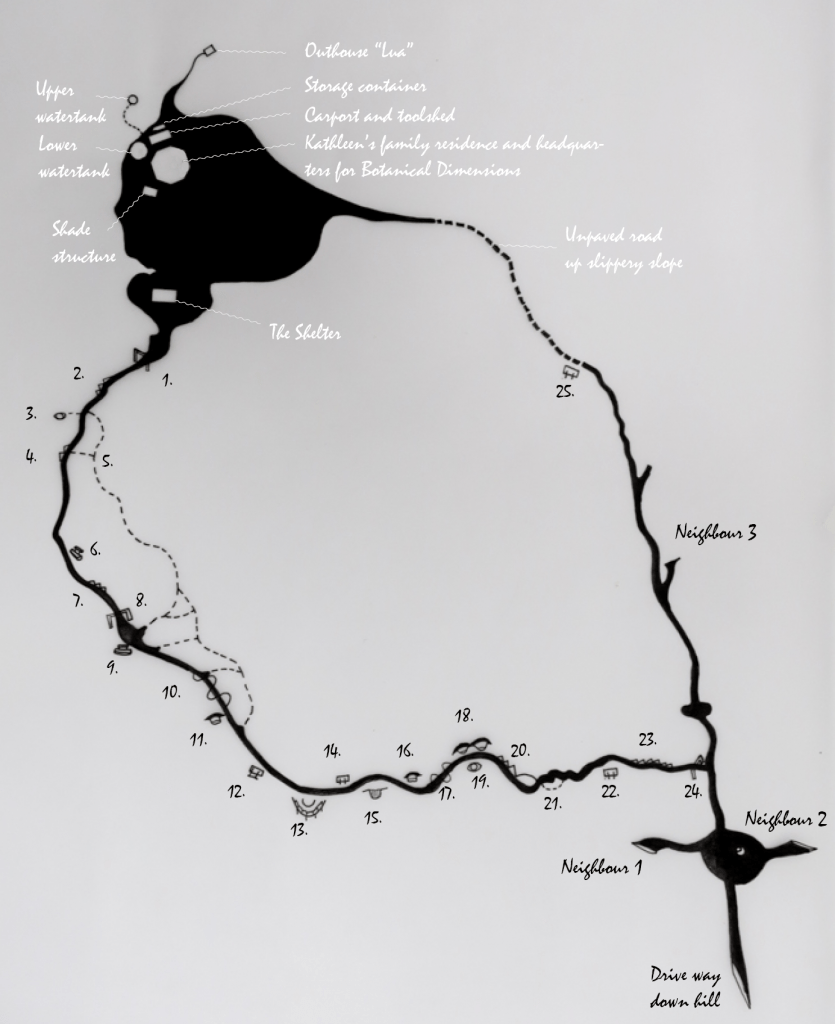

The trail is a 1300 meter long hike through the jungle along a narrow path. In its heyday it was wide enough for two wheelbarrows to roll down abreast. Unfortunately, very little development has been done during recent years, which makes it difficult to maintain. In some places trees and tree ferns have fallen over the path, in others invasive plants are covering the landscape to an impenetrable degree. In order to conduct our field work, and as a service to Botanical Dimensions and the land, we removed invasive species from the trail and around specimen plats. General maintenance of the place was part of our trade agreement with Kathleen.

While locating specimens and taking samples we have kept an eye out for parts of the trail that are in particular need of structural development. The land is also prone to erosion, and wild boar wreaking havoc as they search for food. In some places we built little stairs and retaining walls, to make our fieldwork less hazardous. Yet out here makeshift solutions are but a short time design, proper landscaping (like retaining walls, stepping stones, stairs and handrails) is vital for long term sustainability, and to facilitate maintenance efforts. Below is a map that indicated locations where minor landscaping and carpentry improvements would be appropriate. The dashed side trail #5 was opened up by us as we followed the spread of a certain species along the side of the trail.

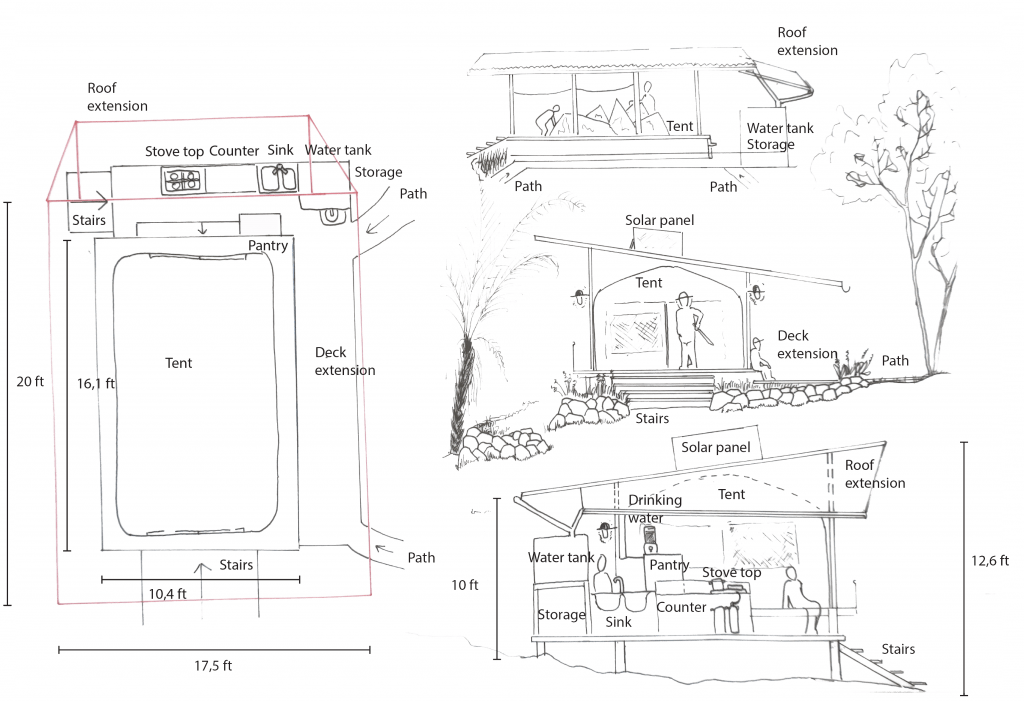

The Shelter is the newest structure developed on the Hill. It is located at the top entrance to the trail, and offers visitors and collaborators a modest guesthouse to stay in. It is however fairly incomplete, since it offers no other facilities (such as kitchen and hygiene), nor is there any space left on the platform to lounge on after erecting the tent. And the mosquitoes are savage, with plenty of puddles to procreate in! While living there we sketched some design ideas on how to further develop the shelter in order to make it more user friendly for future guests. The recent addition of this shelter (only a couple of years old) provides Botanical Dimensions with the possibility of hosting volunteers, workshop leaders and other individuals that may wish to visit, explore and care for this living archive of culturally and medicinally significant species, and their lore.

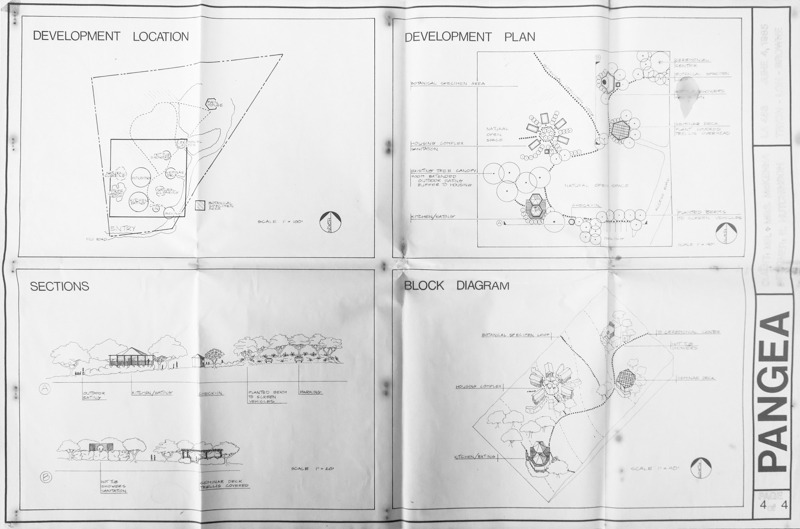

Pangea, derived from the Greek pangaia, bears the meaning of “all the earth”, a term coined by German meteoroligst Alfred Wegener in 1912. Wegener named the supercontinent he proposed existed between 300 million up until 200 million years ago, Pangea [6]. In Elizabeth Hutchinson’s design for Botanical Dimensions, which was never to be implemented, the concept was to plan a variety of spaces and facilities for group activities within the rainforest setting. The idea was that this would enhance the sense of community and belonging, as well as inspire joyous participation in nature. Hutchinsons objectives were: to create a continuous design on the character of the place; to have as little of an impact on the environment as possible; to add native and other appropriate tropical plants; to use design elements which enhance the out-of-doors atmosphere; and to use only locally sourced/indigenous materials.

In her design, Hutchinson lists: parking spaces for six vehicles; a 100 sq. ft. check-in building; a 600 sq. ft. kitchen building with outdoor sitting area for 20 people; housing for 20 people; outdoor baths and showers; an 800 sq. ft. seminar deck; and four sanitation buildings. Considering the current state of Botanical Dimensions, 35 years later, I can barely explain how heart wrenching it is to look at these fantastic designs, and what this place could have become, if Hutchinson’s design would have been taken seriously. Perhaps some day the place will take on new chapters of development, and perhaps these designs will resurface then, and point to possible ways forward. Until such a time they await patiently, hibernating silently along with many other dreams and visions of the Harrison-McKenna legacy.

[1][4][5]https://spark.adobe.com/page/stdre99J3hhXH/

[2]https://www.archdaily.com/155224/vernacular-architecture-and-the-21st-century

[3]https://health.hawaii.gov/docd/disease_listing/rat-lungworm-angiostrongyliasis/